In the utilities and services sector, mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures are now a standard way to grow and adapt in a highly regulated, capital‑intensive environment. It is not uncommon for utilities and services organizations to acquire new systems or smaller companies to add to their offerings, and every one of those moves has direct consequences for core systems, data, and reporting.

Growth through M&A: Technological implications for buyers

In simple situations, adding a new system can be handled through manual entry or limited integration, feeding the necessary data into existing platforms. That approach breaks down quickly when an entire company is acquired or a significant part of the business is sold. What looks like a strategic transaction on paper becomes, in practice, a collision of ERPs, general ledgers, billing systems, payroll, and reporting tools.

Selling part of the business is usually the easier side of the equation. The seller can carve out the relevant service orders, customer records, and financial data from their systems and transfer them as part of the deal. The real complexity typically appears on the acquisition side, where the buyer must absorb an entirely new technology landscape and still deliver reliable service and accurate reporting.

Why core systems become a bottleneck

The acquired company may be using a different ERP, multiple general ledger instances, separate payroll systems, and its own reporting tools. Each system encodes local practices and regulatory assumptions built up over many years. Consolidating these platforms is imperative for coherent service orders and customer support, but it is especially important when trying to see a holistic view of the combined organization’s financial statement.

Full assimilation of financial systems into a single software platform can take months – or even years – particularly when both organizations have been operating for 20+ years with heavy customizations. Public and regulated utilities cannot simply delay consolidated reporting while they sort out their systems. Financial reporting and analytics cannot wait for platform consolidation; they must be delivered while the underlying landscape remains fragmented.

Consider a straightforward, anonymous example.

A 25‑year‑old electric utility operates in one state on a legacy on‑premises ERP and general ledger, a single customer billing system, and a homegrown data warehouse that feeds financial and regulatory reports. The systems are old but stable, and the finance team understands them well.

This utility acquires a 20‑year‑old regional services company that operates across several neighboring states. The acquired company runs a newer cloud‑based ERP, a different general ledger, its own payroll system, and multiple reporting tools tailored to local finance teams.

Once the deal closes, the combined organization is expected to produce consolidated financial statements, demonstrate to regulators that customers will not be harmed, and track acquisition‑related costs and synergies. Under the surface:

- The two charts of accounts do not match.

- Profit and cost centers are defined differently.

- Business units and regions are reported using inconsistent structures.

The initial instinct may be to pick one ERP as the “winner” and move everything onto it. In reality, regulatory timelines, internal readiness, and project complexity mean that full system consolidation will take years. The organization needs integrated reporting long before that happens.

When implemented properly to manage the consolidation of data from the disparate systems, the reporting and analytics tools would need minimal, if any, rework once the financial and operational systems are consolidated to their singular system, as all the business logic and presentation of information would already be standardized, regardless of final system choice.

Why a scalable data strategy must come first

At this point, a scalable data strategy becomes essential. It is paramount for the organization to define how it will handle financial data before committing to a single “forever” system. That strategy should include:

- Decisions about what will eventually become the system of record for all financials.

- A clear approach to standardizing key structures such as the chart of accounts, profit and cost centers, and organizational hierarchies.

- A plan for maintaining reporting and analytics throughout the transition.

Once this strategy is defined, modern data modeling and analytical tools can blend data from multiple systems into a singular, consolidated view of the organization’s financials. This approach often proves to be more optimal and efficient than trying to force all logic into a single transactional system. Even after financial systems are fully consolidated, keeping a central, model‑driven data layer simplifies reporting and supports future changes.

Why manual data entry is not enough

Many organizations attempt to bridge the gap manually. Finance teams extract financial reports from each system, paste them into spreadsheets, and develop elaborate workbooks to reconcile numbers and adjust mappings. This can offer a short‑term bridge, but it is an extremely time‑consuming process that is prone to errors.

Spreadsheets are fragile, with complex formulas that are easy to break as structures evolve. They are hard to audit, making it difficult to demonstrate data lineage to regulators or external auditors. As the number of entities, reporting requirements, and integration steps grows, spreadsheets become increasingly difficult to scale.

During acquisition periods, when teams are dealing with unfamiliar systems, evolving procedures, and new reporting requirements, the risk of human error is especially high. Relying on manual consolidation at that moment introduces risk exactly where accuracy is most critical.

Automation, auditability, and regulatory confidence

Automation reduces this risk by enforcing consistent rules and providing traceability. Modern data tools can automatically extract data from multiple ERPs and general ledgers, apply transformation and mapping rules, and load results into a centralized repository.

This automation enhances compliance for regulatory reporting by maintaining proper audit trails. Every step in the process can be traced, making it easier to confirm that the correct procedures have been implemented and followed. When issues arise, a centralized transformation layer with clear lineage makes it much easier to identify and correct problems than combing through dozens of manually edited files.

For utilities under close regulatory oversight, this level of transparency is not just helpful – it is essential.

Normalizing charts of accounts and hierarchies

Whenever two or more independent organizations are combined, there must be a structured exercise to align and normalize the underlying data structures that support consolidated financial reporting and analytics. Some of the core challenges include:

- Aligning the parent and acquired company’s chart of account data.

- Harmonizing the organizational hierarchical structure as it relates to profit and cost center definitions.

- Reconciling regional, business unit, and service definitions.

Modern data modeling tools and financial consolidation platforms help automate this work. They create transformation rules that convert the acquired company’s account structure into the parent company’s standardized format. These rules can map multiple legacy accounts to a single consolidated account, apply consistent cost center hierarchies developed by the parent organization, and evolve as the combined business changes.

In the case study scenario, both the single‑state utility and the regional company keep their existing ERPs for a period. Data from both flows into a shared consolidation environment where chart of accounts and cost centers are normalized. Leadership sees a single income statement and balance sheet for the combined entity, while still being able to drill down by legacy company, region, or line of business.

Using modern data technologies to bridge the systems gap

Addressing these challenges at scale requires a modern data architecture. Utilizing today’s data technologies, an organization can efficiently transform and migrate data to a cloud infrastructure designed to be the backbone of reporting and analytics.

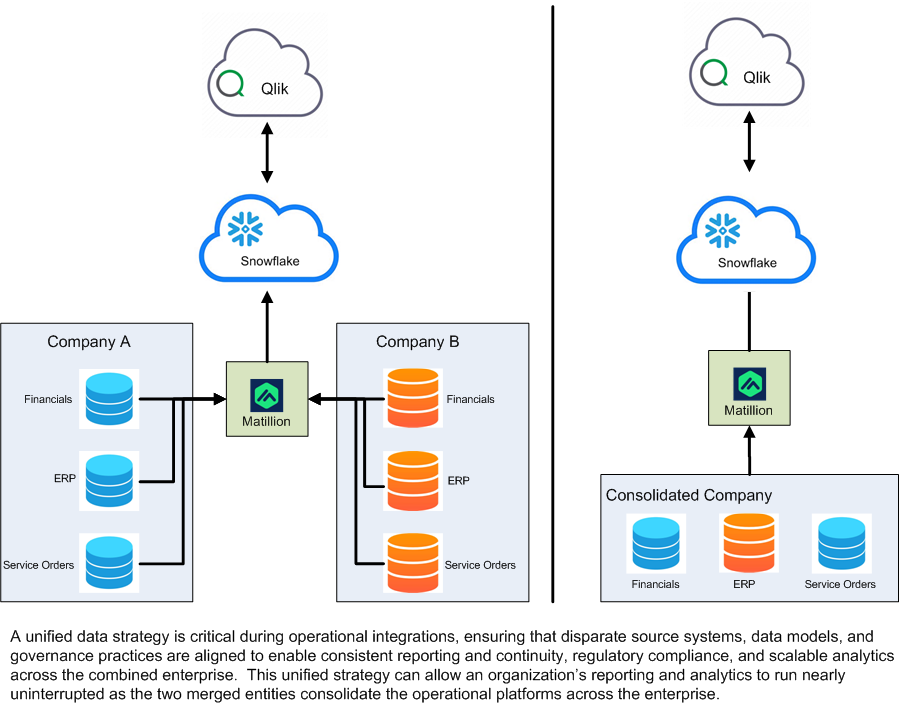

Tools like Matillion or Talend can be implemented to migrate data from multiple legacy platforms and integrate it into a cloud warehouse such as Snowflake. In this architecture, transformations, mappings, and normalization of key data points are processed in a central, controlled environment. The cloud warehouse becomes the singular repository for reporting and analytics.

On top of this repository, a visualization tool such as Qlik Cloud can be used to develop the analytics and presentation of metrics needed for internal operations, financial reporting, and regulatory compliance. Executives and managers work from dashboards backed by consistent, consolidated data rather than a patchwork of local reports.

The crucial benefit is that all of this can be accomplished without waiting for the consolidation of disparate systems and platforms. While long‑term system decisions are being worked through, the organization still has a reliable, unified view of its financial and operational performance.

Building a modern data architecture for long‑term value

Beyond the immediate benefit of automating reporting processes, consolidating data into a modern architecture allows financial and operational data to be centralized into a cloud data warehouse or data lake, even if the operational software platforms remain partially fragmented.

This consolidated data environment supports:

- Financial reporting across the combined organization.

- Post‑acquisition integration analysis, including tracking of synergies and integration costs.

- Identification of cost‑saving opportunities and areas where operations can be streamlined.

In the earlier example, once both the legacy and cloud ERPs feed a shared data platform, the combined company can compare pre‑ and post‑acquisition performance, see where overlapping functions exist, and identify where to standardize practices. That insight turns integration from a purely technical exercise into a driver of real business value.

Turning insight into action – and what to do next

For buyers, the core message is straightforward: the value of an acquisition depends not only on the assets and customers being acquired, but also on how quickly and reliably the combined organization can see and manage its financial performance. Asking early, specific questions about data strategy, systems of record, and reporting architecture is just as important as examining physical infrastructure and regulatory risk.

For IT teams, success depends on defining a scalable data strategy early, reducing reliance on fragile manual processes, and building a cloud‑based architecture that supports both current reporting needs and future platform changes. Core systems can be modernized over time, but the reporting and analytics layer must remain stable and trustworthy throughout.

If your organization is planning or undergoing M&A and you are grappling with legacy systems, overlapping ERPs, and growing reporting demands, now is the time to put a structured approach in place.